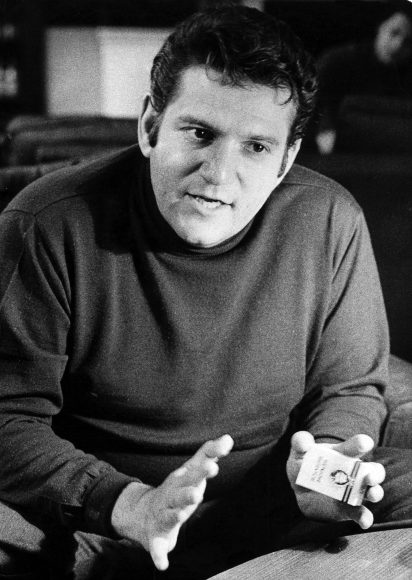

The notorious and pugnacious manager of artists including The Rolling Stones and Sam Cooke, Allen Klein took control of The Beatles’ business affairs in 1969, following the death of Brian Epstein.

Born in America on 18 December 1931, Klein was the son of Jewish immigrants from Budapest. As a teenager he excelled at mental arithmetic. After graduating from Upsala College, New Jersey in 1956, he began auditing for record companies and bookkeeping for a number of showbusiness names.In 1957 he began a business partnership with his wife Betty. Two years later he met singer Bobby Darin at a wedding, and offered to make him $100,000. Darin asked what he needed to do, and Klein reportedly said: “Nothing. Just let me go over your accounts.”

Klein pursued Darin’s record company for money he regarded as owed to the singer. Darin gave Klein free rein to audit his accounts, and duly received the cheque Klein had promised.

The hostile approach became Klein’s trademark. He picked up further celebrity clients, and record labels began to fear his methods.

In 1963 Klein became Sam Cooke’s business manager, negotiating an unprecedented agreement between the star and the music industry: Cooke ended up with the rights to all his future recordings, gate receipts for concert, 10% of all record sales and back royalties.

The deal had a huge effect on the music industry, though it’s worth remembering that he was far from the only management svengali around at the time. Andrew Loog Oldham, for example, secured ownership of all The Rolling Stones’ master tapes, which he then leased to Decca; a method he picked up from Phil Spector.

When Oldham fell victim to drugs in 1965, Klein took over management of the Stones’ affairs. Jagger, initially impressed by Klein’s business skills, recommended him to Paul McCartney, who was looking for someone to take over The Beatles’ business matters. Klein met John Lennon on the set of the Stones’ Rock And Roll Circus, but they didn’t discuss business and little came of the meeting.

The Rolling Stones soon began to doubt the trustworthiness of Klein. They decided to fire him in the late 1960s, and in 1970 set up their own business. However, a legal settlement left Klein the rights to most of their songs recorded before 1971.

With The Beatles

Shortly after the recording of Rock And Roll Circus, Allen Klein read a comment by John Lennon that financial problems at Apple Corps would leave them “broke in six months”.

The Beatles had been without a manager since Epstein died in August 1967. Although NEMS, headed by Brian’s brother Clive, had looked after the day-to-day running, and Paul McCartney was mostly steering the band’s artistic direction, there was little grasp of the bigger picture. There were, crucially, few people trusted to sort out the practicalities of business as Epstein had done.

By 1969 it was clear that Apple’s finances needed to be addressed urgently. McCartney favoured his father-in-law Lee Eastman, but the others – led by Lennon, who on 28 January had appointed Klein his personal advisor on the spot after a meeting at the Dorchester Hotel in London – objected. They felt that Eastman would put McCartney’s interests ahead of the rest of the group.

Klein offered to take a commission only on The Beatles’ increased business, a change in his normal method of operating. If Apple continued losing money, he said, he would take nothing.

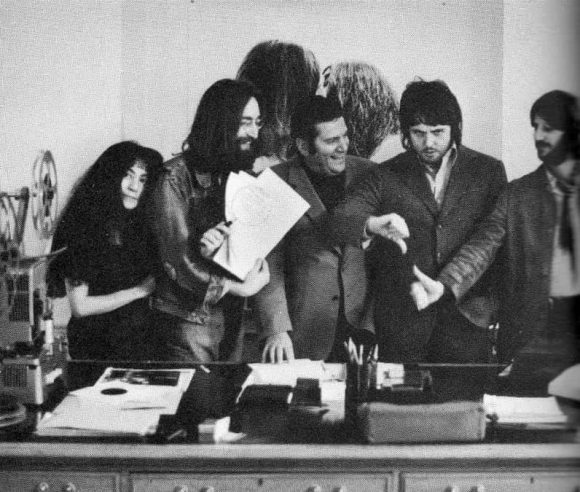

With Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr united, Paul McCartney agreed to pose for photographs with Klein as a sign of unity. However, although he pretended to sign a new contract, he never put his signature to it. The subsequent fall-out over the management of the group was one of the key factors in their break-up.

Allen Klein swiftly renegotiated their EMI contract, obtaining them the highest royalties ever paid to an artist at the time. EMI, in return, were allowed to release Beatles compilations, which Brian Epstein had always resisted.

The single ‘Something’/‘Come Together’ was released on 31 October 1969. Until then, The Beatles had never lifted a single from one of their albums; they had either been stand-alone, or released on the same day as their parent album. The release illustrated the band’s shifting attitudes towards money-making and artistry.

Klein’s action gave The Beatles a hit and some much-needed income. He also helped resurrect the abandoned Get Back project, which became Let It Be. Klein brought Phil Spector to England to work on it, a move which led to years of resentment from Paul McCartney.

Apple Corps was overhauled, and Klein drastically cut expenditure, cancelled charge accounts for many staff and friends of the band. Although in many ways necessary, Klein’s business ethos was in stark contrast to the anything-goes attitude with which Apple was set up. He alienated many of those who had previously been part of the band’s circle, and fired Epstein’s long-standing assistant Alistair Taylor.

He also closed the loss-making experimental and spoken word imprint Zapple, which only released two albums: Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Unfinished Music No 2: Life With The Lions; and Harrison’s Electronic Sound, which carried the liner note, “There are a lot of people around, making a lot of noise; here’s some more.”

Although McCartney deeply distrusted Klein, he admitted to him, “If you are screwing us, I don’t see how.” McCartney went on to sue the other Beatles in order to dissolve The Beatles’ business partnership.

The solo years

After The Beatles split up, Allen Klein assisted John Lennon and Yoko Ono in the making of the Imagine film, and helped George Harrison organise the Concert for Bangladesh. The concert’s financial arrangements led to a breakdown in relations with the former Beatles.

Rather than arrange payment and agree amounts with UNICEF beforehand, Klein had waited until after the concert, which led to questions about the amounts raised and a US tax investigation. Although some funds went to UNICEF at the time, additional amounts were frozen until the 1980s. Klein was also accused of keeping money from the live album.

Klein had also agreed with Harrison that Ono shouldn’t perform at the concert, which led to a breakdown in Klein’s relationship with Lennon. Klein was fired, but sued Lennon, Harrison and Starr for $19 million. In 1977 he settled for $4.2 million.

Lennon’s 1974 album Walls And Bridges contained a song, ‘Steel And Glass’, which attacked Klein.

My Sweet Lord

An interesting footnote concerns George Harrison’s 1971 hit ‘My Sweet Lord’. Harrison was sued by Bright Tunes Music due to the song’s similarity to The Chiffons’ 1963 song ‘He’s So Fine’. Although he said he “wasn’t consciously aware of the similarity”, he was later found to have “unintentionally copied” elements from the song.

Allen Klein supported Harrison during the early stages of the lawsuit, and following the judgment advised him to offer to buy Bright Tunes as part of the settlement negotiations. When The Beatles collectively sued Klein, however, ABKCO chose to outbid Harrison for Bright Tunes.

In 1978 Klein paid $587,000 for the copyright of ‘He’s So Fine’. Therefore, Klein became Harrison’s legal opponent; in effect, he was attempting to buy the lawsuit in order to get damages he knew Harrison would have to pay.

Judge Owen later ruled that Klein had unfairly switched sides, and that he shouldn’t profit from the judgment against Harrison or from the purchase of the song rights. Klein was awarded $587,000, to be payable by Harrison to ABKCO. In return, Harrison got the rights to ‘He’s So Fine’.

As an aside, the demo version of ‘Beware Of Darkness’, from All Things Must Pass, is said to contain lines written about Klein:

Watch out now,

Take care

beware of soft shoe shufflers,

Dancing down the sidewalks.

Pushing you in puddles

in the dead of night,

Beware of ABKCO.

Allen Klein died on Saturday 4 July 2009 of Alzheimer’s disease, at his home in New York City. He was 77.

News flash! Allen Klein just died today (7/4/09) of Alzheimer’s. Hard to believe that this, Michael Jackson’s death, and Phil Spector’s life sentence for murder all happened in so short of a time. Paul’s probably laughing his butt off at the moment! Vengeance is now complete! Rock on, Beatles fans of the world!

allen klein was the anti-thesis of the soul of rock n roll. he was the counterpart to soul, he was the ruthless objectifying capitalist. He took soul and distilled out money, and drooled as a vulture saunters over carrion. He is the real life version of Fagin, or Mr. Smallweed in Dickens books. I wonder if this guy ever helped anyone less fortunate than himself. Another banal consumer that sucks everything he can out of the world. They are all too frequent anymore.

How did he do this exactly?

The Allen Klein saga in the Beatles (and solo years) is one of the more fascinating elements of the break-up.

No matter how you cut it, John let the Klein brigade getting George and Ringo on board, isolating Paul – Paul was then pushed into the arms of his in-laws another uncomfortable position for George and Ringo.

All of this happened during John’s heavy heroin phase – making him impossible to reason with.

The truth is that Klein played John like a cheap fiddle – and this only added to the animosity between John and Paul – thus not only helping to end an incredible partnership – but splitting up two very close friends.

The lose of the friendship between John and Paul is the really sad point. I don’t know about you, but good close loving friends are hard to find.

I’m not saying Klein broke the Beatles up – but he sure made it harder for them to get along.

One point Paul makes often is that previous to Klein everything they did was as friends – all in or nothing.

Klein turned the four of them into voting blocks, and they began to treat each other as business partners and not friends.

Klein was a cancer, and John brought him in – so sad.

Hogwash. Paul’s attempt to wrest control of the Beatles away from the other three, well planned and well thought out, led to Kein being brought in. Yes, the fox got in the henhouse and John and the others greeted him, but Paul opened the door by his machinations and business acumen, which the others clearly lacked. To hear this dribble about the artistic destruction of the group being wrought by Lennon and the other two is sickening really. But I can see how the simple minded can be seduced by this specious argument.

On 8th of April 1973 John uttered the words “possibly Paul’s suspicions were right” in an interview on Weekend World(it can be seen on YouTube, perhaps even elsewhere)concerning his firing of Klein(or not renewing his contract).

I would have found Klein’s firing and John’s quote, had I been Paul, as a complete vindication.

There were clearly many factors at work that brought about the end of the Beatles and your attitude towards others whose interpretation of events is different to yours is condescending. Your agenda in attempting to blame one individual over another is no different from anybody elses. The ensuing emotional disarray within the band was advantageous to both Klein and the Eastmans. McCartney did have more savvy in business matters – if he had perhaps reluctantly and anxiously agreed to Klein’s management no doubt the others would have got cold feet and pulled out. In the end, all of them put their long and close friendhip behind business differences, royalties and endless legal battles. Was it worth it?

I agree. If you look at the way Apple was run you could say none of the Beatles were any good at business. Although well intentioned and idealistic in giving artists a break without them having to beg to an executive being creative and musical gods doesn’t necessarily mean you can keep a tab on costs.

I know that was a point brought up in Alex Winter’s Frank Zappa doc. Zappa had interest in the business side, especially in the autonomy it gave him against those who might take advantage of him/the Mothers. When he met The Beatles, he was taken aback by just how uninformed and uninterested they were in it at the time.

Hogwash, Doug. That’s a work of pure assumption and fiction. You weren’t there. You don’t know any of them and you have no inside information.

Case closed.

Excellent analysis, Robert. A good solid A grade for you.

He was not like cancer which there is use for.

He was like a drug which has use but over time does more damage then help and is very difficult to end use of.

Yep. Analagous to what Ray Danniels did to Van Halen after Ed Leffler died.

Again – why would the other 3 Beatles want to be managed by Paul’s father and brother in law. Klein got them a better contract and he almost got them Northern Songs. HE got rid of Nemperor Holdings AKA Clive and Queenie Epstein taking 25 percent for doing nothing.

Klein get’s the Yoko Ono bad rap award from Macca.

A evil in the Beatles story.

Why? He got them more money than they ever had. Paul didn’t like him and he want his own Father in Law to run the show.

As Paul is still alive he is running around blaming Klein for the break up.

I think you’re all being a bit tough on old Kleinster. There was one side that was released but from Kleins perspective he was trying to protect their musical inventory and keep it within the apple family. He did a great job pushing them musically and ran Apple like business (which is something the Beatles were not able to and they admitted this). The Beatles nearly lost everything to do their own mismanagement. Once they got Klein out they lost their catalog to Whacko Jacko.

John and Paul accepted stock in ATV for their share of Northern Songs in 1969 after Allen Klein failed to obtain majority ownership of Northern Songs for Lennon & McCartney.

After this transaction took place, it was ATV that sold control of Northern Songs to Michael Jackson in the 1980’s.

He did what any manager would have done and there were no shortage who would have loved to manage The Beatles. Did he do it better than another could is the question but in the end Klein answered it by acting like a jerk.

Klein was a thief and crook. When he got a new royalty agreement, he was contracted by John, George, & Ringo to receive 20% of the INCREASE in royalties. It was discovered when Paul sued that he was illegaly taking 20% of ALL their royalties. He also wanted royalties on Paul’s album McCartney. Paul disputed this & the albums royalties were being held by EMI until the issue was resolved. Yet Klein went and illegaly took his clained share of these royalties from APPLE. He did much more!

I’m starting to think Paul McCartney and Allen Klein knew what they were doing.

Alan Klein was never ‘the Beatles’ manager you should correct that. He was John’s manager and soon after he became John, George and Ringo’s manager but he was never Paul McCartney’s manager and that was the material point. Once different parts of the band were under different management the whole situation became unworkable. That was the beginning of the end, It all unraveled after that unilateral January 28 1969, decision.

Somebody brought Klein in, and I think that’s McCartney.

In June of 1966, Allen Klein announced his intentions to manage The Beatles. What was going on around the same time was that Epstein seemed to be taking his time renewing The Beatles contract with him. One which he did not sign, which allowed them to walk freely from his management at any time they chose without legal repercussions.

Come November 1966, Epstein seems to be getting a handle on that contract renewal, but what also appears is an article stating two of The Beatles have approached Klein for management. Which two Beatles? Who knows. Epstein, Lennon, Harrison and Starr all deny the claims. McCartney? He’s in Africa and can’t be reached. (Kind of like those missing statements about Epstein’s demise from him, but comment from the other 3 when it happened.) In Christopher Sandford’s “McCartney” he makes mention that McCartney sought out Klein in 1966, which would make sense. He’s the only one not around when Klein says Beatles are abdicating Epstein’s kingdom!

Ironically, The Beatles animated series from season 2 shows McCartney as The Beetle Killer. Now I’d have to work out when that episode premiered on a Saturday morning in 1966, but since most shows in North America begin their seasons in September, I’m sure we could work out when The Beetle Killer made his first appearance, and if that is well timed with Klein’s true arrival, which was in 1966. Not 1969.

DrTomoculus, It was John Lennon who bought Klein in. Paul hated Klein and would not sign him on as Manager.

Lennon brought klein in to sort out the mess inherited from epsteins shambolic financial management of the group. To a large degree klein was successful and got the group a vastly improved royalty rate and got their revenue streams and spending under stricter control. Even mccartney admitted the deals were good. Unfortunately this meant klein had to be brutal with apple which didn’t help the groups already fractured relationships.

Ultimately though john knew klein would not be acceptable to paul as a business manager (the eastmans were among those that warned him off) and he kind of revelled in how much it wound mccartney up. He absolutely despised lee eastman as a person never mind the idea of him being the groups manager. being Johns attraction to strong,charismatic figures was always an achilles heel and it came home to roost here. Klein had done his homework this time and as someone above said “played lennon like a fiddle”.

Ultimately he was just too brash and fly by night a character to manage a band like the beatles. As the others found out to their cost.

Brian Epstein was not a bad manager – that description is more applicable to Stan Polley, the crook who mismanaged Badfinger – and he was also managing other clients besides The Beatles, something that these biographers who unfairly criticize him by sensationalizing or exaggerating his faults at the expense of his good points fail to mention.

Brian did not overwork The Beatles to the point of exhaustion and he allowed them to take nice holidays whenever they needed them. Even on their American tour of 1965, he let them have at least 5-6 days of R&R and they got to meet Elvis at his home in Los Angeles.

He also bought guitars for John and George and drums and a car for Ringo which does not match the description of a bad or hopelessly inept manager.

It is perhaps rather telling that Peter Doggett has written that no such rehabilitation was ever afforded to Allen Klein the way that it was for Linda and Yoko.

It seems that Klein was a very good business manager for the Beatles but Paul hated him from the beginning. And yes, firing Apple Employees may have made sense but not a good idea.

If they never released singles off albums then someone explain Help! and Ticket to Ride – both from the same album

A similar thing occurs on A Hard Day’s Night as well.

Yellow Submarine / Eleanor Rigby being another.

On the subject of Klein, how exactly did he screw the band ?

The singles from AHDN and Help! were released prior to the albums coming out, and Yellow Submarine was released on the same day as Revolver. However, Something was released after Abbey Road had already been out for a few weeks, which is what they hadn’t done before. It’s a distinction people often fail to make regarding this matter.

Oh John. You’re so sweet! It’s because Help and Hard Days Night were both films (movies). I think if you looked deep down you already knew this answer

Any Singles from an album were usually released at the same time as the album, not later as usually happpens when a new album comes out.

and Lady Madonna and many more singles

Lady Madonna was a stand-alone single. It only much later appeared on compilation albums.

I few years back I posted on here and asked how exactly Klein was meant to have screwed the band. There has been no answer forthcoming.This confirms my suspicions. He didn’t but it suited some people to portray him as a villan in order to justify certain aspects of the Beatles demise.

Someone wrote this further up on this page: ‘When he got a new royalty agreement, he was contracted by John, George & Ringo to receive 20% of the INCREASE in royalties. It was discovered when Paul sued that he was illegaly taking 20% of ALL their royalties.’

When George was losing the My Sweet Lord lawsuit, Allen Klein switched sides, and bought the rights to He’s So Fine[or rather, ABKCO outbit George in the sale of Bright Tunes], in the knowledge that George would have to pay up. In the end he didn’t get away with it, but it appears a bit scumbaggy.

Can’t see the forest for all the trees?

there are plenty of answers to your question. Klein was a scumbag. Thank you and goodnight

He got them more money than anybody in the past. And no there doesn’t seem to be allot of reason why he is the Bad Guy except that Paul hated him.

Again, Klein did not screw over the Beatles. He took 20 percent which is a standard rate. He upped their income and he tried to get their publishing royalties back, the fact that Brian Epstein screwed that up.

What the cancer is =: McCartney didn’t want him and never wanted him. And as others posted, it was supposed to be all in or all out.

Why would the other Beatles want McCartney’s Father in Law and Brother in Law to run the show. There would be zero trust on that too.

FYI, Brian did renegotiate both the merchandising deals and the band’s EMI contract, so he was clearly not a bad businessman.

None of the Beatles had any unkind words to say about Brian in the Anthology documentary and the footage of them after hearing of his death shows how devastated they were. Paul acknowledges that while it was very sad to lose Brian in the way that he did, he did say that they didn’t think not having a manager was a major issue.

Brian lost them over a billion dollars.

A. He and his family took 25 percent and somehow Klein getting 20 is wrong?

B. The merchandising deal lost them 100 million in 1964 dollars.

C. The record deal with EMI was horrible.

D. The publishing deal with Dick James was horrible.

That is what destroyed Lennon and McCartney in the end.

Eastman versus Klein was the result of Epstein’s terrible deals.

FYI, Brian did renegotiate both the merchandising deals and the band’s EMI contract and none of the Beatles had any unkind words to say about Brian in the Anthology documentary.

I think it’s easy to see how Allen Klein and Yoko Ono selfishly stroked Lennon’s fragile ego for their own greed. Lennon was very impressionable. Klein already raped the Stones and now sought to manipulate Lennon for more. He got Lennon and Yoko to fight against his band members to allow him in. Then in 1973 Lennon and Yoko went on TV saying Paul was right all along about Klein. During this time Lennon tried to escape Yoko but she sucked him back into her web.

Lars, I just want to tell you that i think your knowledge of the Beatles is amazing. I just got am email back from Mark Lewinsohn which was great – maybe you could help him research the new volume after Tune In (probably Turn On). May I ask you question – do you or any Beatles fans know what happened to the lorry that Lennon and the others used to get to Woolton church fete?

Best wishes

Chris Walker

Leeds, England

Jack… https://youtu.be/3bxwaNUVHQQ Listen to how Klein was involved in stealing and renaming a Frank Zappa and the Mothers song and giving the writing and producing credit to John.

So, Brian Epstein’s death lead to a slow 3 year demise of the Beatles.

There were now leaderless, unable to function as a group.

Sadly, you are right. I believe that, in hindsight, The Beatles should’ve taken Mick Jagger’s warnings seriously – Paul certainly did – and avoided Allen Klein altogether in favour of Paul’s father-in-law Lee Eastman, given that he and his son John, Linda’s brother, represented him after The Beatles and Paul no doubt became a better businessman thanks to his in-laws, something that he himself acknowledged in 1984 by citing one piece of crucial advice from Lee about publishing.

It does not surprise me that Klein did time in jail for tax-related crimes.

Paul McCartney was the only one that didn’t sign with slippery Klein. Not only was Paul McCartney an amazing songwriter and musician, he knew that Klein was a creep and tried to tell John, George and Ringo to not sign with him. However, John was to naive and pushed George and Ringo into signing with the creepy Allen Klein. Paul was So Right about Klein, Spector and others that ended up screwing the other Ex Beatles. Luckily Paul sued Klein and today the Beatles own their music because of it. The Rolling Stones weren’t as lucky and Klein’s company owns a lot of the Best Albums.

AGAIN, every story you read about Klein is that he got the Beatles more money and royalties than ever before.

1) Paul hated him from the start for whatever reason.

2) He screwed up the Concert for Bangladesh, 2 years later.

3) In 1973 after firing Klein they say Paul you were right.

Somebody needs to do real research. The 4 Beatles had too much narrow vision and anger and craziness going on.

Again, you are strictly giving McCartney’s version. And Jagger said he may not be your cup of tea, he didn’t say don’t do it.

It is McCartney running around in interviews calling him an idiot and a cancer because he doesn’t want to call out heroin addicted John Lennon, the mistreatment of George, Ringo drinking and making movies.

The dream was over by Jan 69.

There is no documentation that Klein screwed over the Beatles when he was their manager.

1) He did fire the old Apple employees which pissed people off.

2) He took 20 percent of all Beatles Royalties which is the standard fee. The fact that he took the royalties on pre Klein management days is what. He was the their manager for all things not just May 69 onwards.

3) He was brash, arrogant, NY Jewish and UK folks don’t like that.

4) In 1973 the rest fire him. and then revisionist history starts.

DONE, it so frustrating that now Klein is the Cause and before it was Yoko, etc. Rather than themselves.

Actually, Bradley Hurrell is right on a lot of points and even John conceded in a 1973 interview that Paul was right about Klein’s true colours.

I respectfully disagree with you that George was mistreated, because he never made any effort to leave the group except for a few days in January 1969 and he came back.

It was Peter Doggett who said that in contrast to Linda and Yoko, Klein was never afforded the same type of rehabilitation as those two ladies. Mr. Doggett also says that Paul’s moral victory in the debate over Klein creatively liberated him and drove him to make his best post-Beatles album “Band on the Run” plus John, George and Ringo were embroiled in litigation against Klein around that timeframe.

Paul won his case against John, George and Ringo in March 1971 and a receiver was appointed to handle their affairs until a settlement was reached to all four’s satisfaction.

In the tape recording of the Sept 5 1969 meeting in which they discuss their album. John tells George that his music was shiite up until basically 1969. George then lambasts John not caring or playing on his White Album songs. Patti Boyd frequently is quoted as stating how Paul pissed George off.

This is clear, Allan Klein did not break up the Beatles. That is the Macca Excuse. John wanted out, George wanted out. Neither had the balls until Sept 1969. It cannot be easy to break up the biggest group in the world.

Even Macca says that when John moved to the Ono phase he left the Beatles phase. He had moved on. It is hard for all Beatles fanatics to figure that out and accept it.

Macca brings in his own Father in Law to run all their financial affairs just another thing to piss them off.

Actually, I have read somewhere on Quora, I think, that Lee Eastman warned Paul about Klein’s true colours and he obviously took those warnings very seriously.

George’s recollections about his White Album songs were untrue, since John played organ on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” (it’s obvious on Take 27) and contributed tape loops and backing vocals to “Piggies”, but he was absent from “Long, Long, Long” and “Savoy Truffle”, likely due to Yoko being pregnant and going through his divorce from Cynthia.

At the September 1969 meeting, George also incorrectly stated that he never had Paul, John or Ringo backing him up on his tunes and John angrily shot back, insisting that the others had put a lot of work into his tunes. This was true, because John, Paul and Ringo were almost always collectively involved with the recording of George’s songs – you can read more of it on the September 9, 1969 page.

The only song that George wrote and recorded without the others’ participation was “Within You Without You”, but it was his own choice to predominantly utilize Indian musicians and some classical string players.

Pattie wasn’t even a regular at the band’s recording sessions, let alone as frequently as Yoko, so she wouldn’t have been privy to what went on between Paul and George behind closed doors. She said it several years later after George died and he is in no position to negate it – Pattie took drugs, including LSD, and drank heavily in the past, so you can’t expect her memories to be 100% accurate.

John conceded in 1973 that Paul was right about Klein and I don’t believe Paul tried to antagonize John, George and Ringo by wanting to bring in his father-in-law to manage their financial affairs.

The Eastmans undoubtedly helped Paul become a better businessman and he himself has acknowledged a crucial apiece of advice from Lee regarding publishing.

The problem lies with Brian Epstein. He completely screwed up everything, in all areas of their financial situation. But somehow Allan Klein becomes the bad guy who broke up the Beatles. Because the one Beatle left to tell the story is Paul McCartney. Ringo doesn’t bring himself into these discussions of who broke the band, per se.

Arnold

I don’t know what you have against Brian – without him, the world wouldn’t have heard of The Beatles, and he made the effort to help them get a record deal, settling on EMI.

He managed other acts besides The Beatles and when he was alive, John, George and Ringo lived in nice large houses in Surrey (although in George’s case, he had a bungalow) and Paul had a nice 3-storey London house, which he still owns, as well as a Scottish farm, none of which they would’ve realistically been able to afford if they were financially ripped off or screwed.

Please – can anybody give 1 example where Klein screwed over the Beatles in 1969?

Macca wanted his in laws, the other 3 did not.

Epstein brought about the financial mess they were in plus nobody running Apple Corps until Klein fired the lot, which was a good thing.

Klein whiffed on NEMS and Northern Songs right out of the gate. After Seltaeb, the worst moves by the band