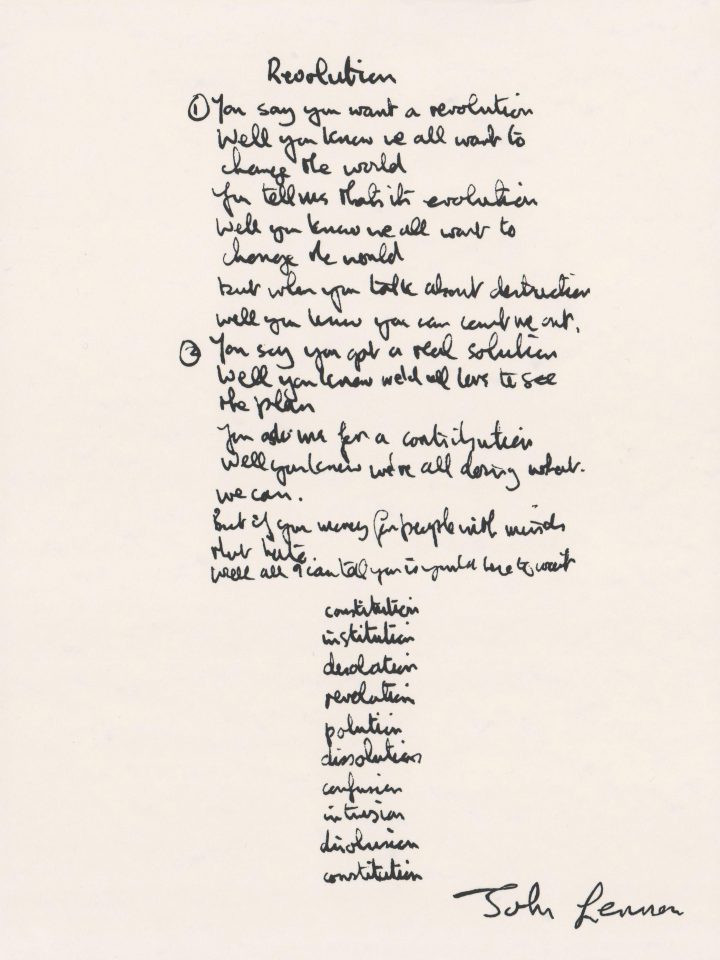

The first song to be recorded for the White Album, ‘Revolution 1’ was written in India in early 1968. It was inspired by the 1968 student uprising in Paris, the Vietnam war and the assassination of Martin Luther King, and heralded a political awakening for John Lennon.

Early 1968 saw a profound shift from the hippy-era’s believe in peace and love, towards political turmoil, protest and struggle. An increasingly politicised and energised Lennon watched the unfolding events with interest, and decided to put his feelings into song, aware of the risk of alienating The Beatles’ fans.

I wanted to put out what I felt about revolution. I thought it was time we f*****g spoke about it, the same as I thought it was about time we stopped not answering about the Vietnamese war when we were on tour with Brian Epstein and had to tell him, ‘We’re going to talk about the war this time, and we’re not going to just waffle.’ I wanted to say what I thought about revolution.I had been thinking about it up in the hills in India. I still had this ‘God will save us’ feeling about it, that it’s going to be all right. That’s why I did it: I wanted to talk, I wanted to say my piece about revolution. I wanted to tell you, or whoever listens, to communicate, to say ‘What do you say? This is what I say.’

Rolling Stone, 1970

The song started life simply as ‘Revolution’. The Beatles didn’t anticipate recording it more than once, and it was only when the other members vetoed it as a single release that Lennon considered the faster reworking for the b-side of ‘Hey Jude’.

When George and Paul and all of them were on holiday, I made ‘Revolution [1]’, which is on the LP and ‘Revolution 9’. I wanted to put it out as a single, I had it all prepared, but they came by, and said it wasn’t good enough. And we put out what? ‘Hello, Goodbye’ or some s**t like that? No, we put out ‘Hey Jude’, which was worth it – I’m sorry – but we could have had both.

Rolling Stone, 1970

Although recorded after ‘Revolution 1’, the faster ‘Revolution’ was released before the White Album. It divided audiences, with many condemning Lennon’s unwillingness to take part in the protests. When he recorded ‘Revolution 1’, however, Lennon was less certain of his position, opting to be counted “out, in”.

Paul McCartney was uneasy about such a political song becoming a single, and with George Harrison’s backing he vetoed Lennon. As a result, the song was re-recorded in its faster form, satisfying Lennon’s wish to see the song on a Beatles single.

The first take of ‘Revolution’ – well, George and Paul were resentful and said it wasn’t fast enough. Now, if you go into the details of what a hit record is and isn’t, maybe. But The Beatles could have afforded to put out the slow, understandable version of Revolution as a single, whether it was a gold record or a wooden record. But because they were so upset over the Yoko thing and the fact that I was becoming as creative and dominating as I had been in the early days, after lying fallow for a couple of years, it upset the applecart. I was awake again and they weren’t used to it.

All We Are Saying, David Sheff

In the studio

The Beatles began recording ‘Revolution 1’ (then simply titled ‘Revolution’) on 30 May 1968, more than three months after their previous recording session at Abbey Road.

Sixteen takes were recorded on this first day. They were numbered 1-18, although there were no takes 11 and 12. The recording had piano, drums and acoustic guitar all on a single track of the tape, and John Lennon’s vocals on another.

The final attempt, take 18, was substantially longer than other attempts. It lasted 10:17, and formed the basis of the album version.

Despite Lennon’s shout at the 7:31 mark, “OK, I’ve had enough!”, the final six minutes descended into a mostly discordant instrumental jam. It included feedback, Lennon repeatedly screaming “All right”, and moaning from Lennon and Yoko Ono. This later formed the basis of ‘Revolution 9’, with the addition of a number of tape loops and sound effects.

Take 18 was released in full in 2018 on the super deluxe 50th anniversary reissue of the White Album.

Recording continued on 31 May 1968, with two separate vocals by Lennon and bass by Paul McCartney. George Harrison and McCartney also recorded backing vocals.

Lennon re-recorded his vocals on 4 June while lying on the floor of Abbey Road’s studio three, in an attempt to make his vocals sound different.

John decided he would feel more comfortable on the floor so I had to rig up a microphone which would be suspended on a boom above his mouth. It struck me as somewhat odd, a little eccentric, but they were always looking for a different sound; something new.

The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, Mark Lewisohn

A number of other recordings were made for ‘Revolution 1’ on this day. McCartney and Harrison taped more backing vocals, singing “Mama, Dada, Mama, Dada” repeatedly towards the end of the still lengthy recording.

Ringo Starr also recorded more drums and percussion. Lennon added a guitar part played through a volume pedal, and McCartney taped an organ part. Two unused tape loops were also made: all four Beatles singing a high-pitched “Ahhhh”; and what Mark Lewisohn describes as “a rather manic guitar phrase, played high up the fretboard”.

An 11-minute rough mix of ‘Revolution 1’ leaked online in February 2009. The mix, numbered RM1, reveals how the song evolved into ‘Revolution 9’, with the extended jamming and various tape loops, and begins with John Lennon announcing “Take your knickers off and let’s go”.

Listen to the mix (the audio cuts in and out before the music begins):

‘Revolution 1’, with its final title in place, was completed on 21 June 1968. Two trumpets and four trombones were recorded, and George Harrison overdubbed a lead guitar part.

The new stereo remastered version is quite impressive! You can here the background talking in the beginning lead guitar fill better. (I still can’t make out what is being said.) Paul’s bass has new texture and clarity making it almost the lead instrument!

I love take 20 of this Revolution 1 song, to me it’s way better than the final version that appeared in the white album, plus it gives more sense to Revolution 9, It’s some sort of prequel if i may say.

The question I was asking to myself was why Geoff Emerick says “Take 2”, when the master version is actually take 18?

As you can hear at the beginning, Lennon fluffed his acoustic guitar riff. Geoff quickly decided that they would start again, but not naming the next take “Take 19”. So when Geoff announces “Take 2 [of take 18]” Lennon says OK and then it started again.

I have the same question.

I didn’t know until now that Francie Schwartz helped with the shoo-be-doo-wop backing vocals. So, that means that all four then-current Beatle wives/girlfriends contributed vocals to the white album! Which is kinda nice.

Nice! I know Yoko and Pattie sang on “Birthday.” I didn’t know about Maureen though. Do you know what tracks she was on?

She sang backing vocals on The Continuing Story Of Bungalow Bill.

Though I like the faster version of this song, I always thought, that the slower version really underlines the message of this song.

The almost provocative slowness supports the idea that aggression and violence aren’t the best choices for getting things changed.

“Don’t you know it’s gonna be alright?”

Revolution 1 (Take 20) is just fantastic. For me it takes the great ideas from Revolution 9 and incorporates them into a truly groundbreaking song. I think maybe if Paul and George weren’t so nervous about putting out a politically charged song it could have been one of the Beatles’ finest.

Well it is anyway. Try listening to Revolution 1 (Take 20) while having a bit of a smoke and get blown away

Lennon thinks his “creativity” was a threat to the applecart at this time? Please. The moment he dove up Yoko’s b-side he stopped being creative and instead became self-indulgent. At least Paul understood, correctly, that he was a songwriter. But Lennon eats a fistful of acid with Yoko and then decides he is not a songwriter but an ARTISTE! Why bother writing songs when you can hand out acorns and hold press conferences while wearing a bag over your head? “What we did, see, was mic up the toilets at Tittenhurst and record Yoko and me takin a s**t, and listenin to it you can’t tell what fart came from which ass. There can be no prejudice, then! It’s total communication!” The guy was a charlatan.

Clearly John Lennon upset your applecart on what you thought he should be. Isn’t that a shame. Everytime you look in the mirror you see a charlatan. Troll.

John Lennon was many things, good and bad. He was mostly John Lennon.

Wtf are you in comparison to Lennon. What did you do to get John Sinclair out of jail. What hall of fame were you inducted into. Your jealousy knows no bounds, let alone your hipocracy, Huckleberry!

I guess ‘Imagine’ and The Plastic Ono Band album, both considered to be two of the finest of the post-Beatles solo albums were just more of the same then?

do you honestly think,honey pie,obla dee obla da,your mother should know,maxwells silver hammer, were creative writting

What about Mr Kite, Good morning, Bungalow Bill, …?

I don’t think Daveroxit was being a troll. I believe the drugs made John insecure and angry at Paul for continuing to be a very good song writer.

I will challenge anyone who comments that John Lennon was a charlatan and not an artist.

If writing about oneself and politics are deemed to be “self-indulgent”, then what are song writers supposed to write about that is real?

As for drugs making Lennon insecure and angry at Paul, Lennon was getting fed up with Paul’s attitude in regards to Lennon songs such as Revolution 1 and Across The Universe.

Your comment about Paul “for continuing to be a very good song writer” implies that John didn’t. I couldn’t disagree more.

In another comment elsewhere, someone posited that John might have been manic/depressive. In one of his last interviews, the way that he described moods that sometimes made him even incapable of dealing with Sean gives some credence to this. John was also quite insecure about his talent at times. The pep talk Paul gives him on the Anthology version of “Julia” gives an indication of this. For me, the thing that dramatically changed The Beatles was overwhelming success of “Yesterday”. In their teenaged years, whenever it looked like some band member could be capable of challenging John’s position as leader, by his own admission, John would usually sack them out of the band (sometimes with an a$$-kicking). The phenomenon that was “Yesterday” elevated Paul to a status nearly equal to John, who had up to that time been the main producer of songs, and often the ones needed on demand like “Hard Day’s Night”, “Eight Days A Week”, and “Help”. On HDN John was the main writer of eleven of the 14 songs. Although he abdicated much of his leadership role to Paul, John was still the unquestioned leader of The Beatles when he put his foot down, partly because he could scare the others sh!tless.

Once again, your blinders-on love of John (and, not incidentally, anti-Paul) belies your ablility to see clearly..

John, like Paul, was not nearly the same songwriter without working with the other.

Some people prefer to attack the arguer rather than the argument. It’s common – like you know, common.

I know a lot about POV. In order to survive in the boardroom of a multi-million dollar corporation, and work properly on budget and editorial committees, one must be aware of the distinction between the presenter and the discussion in question. Not so common a background, like you know, uncommon.

OK. Instead of conducting a pissing contest on my website, could you please keep discussion to the relevant subject (Revolution 1)? Thanks.

What is that sound at the beginning of the song that sounds like ( to me) a washboard or crackling noises?

I’ve always wondered what that sound effect was too. Is it guitar picks on a washboard? I’ve never read anywhere explaining what made up that sound effect. The start to Revolution 1 is so iconic with the slower bluesy acoustic lead in, while the engineer says ” Take two” and followed by Lennon saying “OK”, and of course that unique sound effect. But what is it??

I am currently re-doing all The Beatles songs from beginning to end and am playing all the instruments and adding the appropriate sound effects the best I can. So I had to figure out this crackling noise at the beginning of the song and then replicate it. I asked my wife for some crinkly paper from the kitchen and she gave me a piece of parchment paper – like newspaper but a little stiffer. At the appropriate point I held it up to the microphone and crinkled it. It worked. The sound is exactly like the sound on the album.

With respect, it would be up to Paul, Ringo, or someone who was in the studio to really describe what was happening.

A thought, if you think about the song starting with a failed ‘take one’, then the crinkled paper makes sense. Like an author crumbling up a failed first draft of his lyrics. It fits.

Wow! I really had not read your experiment on replicating the sounds on Beatles songs and I just landed on the explanation of this song here, with my mind on the sound of crinkling paper at the start…and it turns out to be just that! Thanks for the experiment!

When he raked his top fret

After John sings “…but if you talk about destruction, you can count me out”, there is a slight pause and he says “In”. This comment does not appear on the faster single released version. Not quite sure if John is having a little fun or making some kind of additional comment by leaving the door open.

Well, by the time he recorded the single, he probably decided to be definitively counted out, as in non-violent revolution.

But on the David Frost show, they played the single version with added shoo-be-doo-wops and he can be seen and heard saying “in,” somewhat offhandedly.

I remember reading many years ago that John regreted writing what he wrote on the lyrics about Chairman Mao, apparently changing his opinion on revolutionary movements, showing a more left leaning position on politics. Does anyone know or would care to comment on this? Thanks.

That was at the peak of his radical politics period, circa Some Time In New York City (1972). IIRC he said something like “In Revolution I said you won’t make it with Chairman Mao, but look at me now – I’m wearing a Mao badge”. I’m sure someone will be able to source the exact quotation/interview.

From the 1971 Rolling Stone interview with Jann Wenner:

https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/lennon-remembers-part-two-187100/

So that’s my feeling. The idea was don’t aggravate the pig by waving the thing that aggravates – by waving the Red flag in his face. You know, I really thought that love would save us all. But now I’m wearing a Chairman Mao badge.

I’m just beginning to think he’s doing a good job. I would never know until I went to China. I’m not going to be like that, I was just always interested enough to sing about him. I just wondered what the kids who were actually Maoists were doing. I wondered what their motive was and what was really going on. I thought if they wanted revolution, if they really want to be subtle, what’s the point of saying “I’m a Maoist and why don’t you shoot me down?” I thought that wasn’t a very clever way of getting what they wanted.

I’m sure the Chinese would agree with John

‘So that’s my feeling. The idea was don’t aggravate the pig by waving the thing that aggravates–by waving the Red flag in his face. You know, I really thought that love would save us all. But now I’m wearing a Chairman Mao badge.

I’m just beginning to think he’s doing a good job. I would never know until I went to China. I’m not going to be like that, I was just always interested enough to sing about him. I just wondered what the kids who were actually Maoists were doing. I wondered what their motive was and what was really going on. I thought if they wanted revolution, if they really want to be subtle, what’s the point of saying “I’m a Maoist and why don’t you shoot me down?” I thought that wasn’t a very clever way of getting what they wanted.’

Rolling Stone Interview, from Feb. ’71

Sorry, Justin. Immediately after I posted my reply above I saw you had already provided the quote three years before.

The Maos children were propaganda

On the 2009 remaster it is well audible – at 00:06, while on the left channel the guitar starts, you can hear on the right channel a woman’s voice saying the german words “Mein lieben Herren Kollegen” (“my dear colleagues”). To me, as german, it sounds like native speaker. Who is this? What is this? Google won’t find it (!), has nobody heard it yet?

-Greetings from Berlin, Germany, Rolf

Does anyone know who exactly is playing the LEAD in this song, like the runs and the little “cheese” licks in between the “you know it’s gonna be” lines?

I think that’s George – the overdub from 21st June 1968, the same day that the brass section was recorded.

Out of all these responses, only one person asks about the crackling noises that appears at the beginning of the song…right after you hear Johns classic “OK”. What makes those noises??!! I would think more people would ask this question since it wasn’t mention in the studio recording of the song above. Is it coins being dropped? Or gravel? It’s such a classic part of the start of this song that helps make Revolution1 so unique, but no one else has asked or talked about it. So how about it Beatle fans… does anyone know what the heck those cracking sounds are at the beginning of the song?!

See my reply above to Pat and Stoutman7777.

While listening to this song a bit ago – I had a weird flash memory to the theme song for Courtship of Eddie’s Father (“Best Friend”) by Nilsson. Just some very – very – slight resonance between the two songs for me.

Revolution Take 20 is a masterpiece. It’s a shame it took decades to be heard. I wonder if Yoko leaked it since she was involved? Take 20 sounds so great without George Martin’s lethargic brass arrangement that does nothing for the song but slow it down.

Revolution Take 20 is a masterpiece. It’s a shame it took decades to be heard. I wonder if Yoko leaked Take 20 since she was involved and probably has one of the only versions? Take 20 sounds so great without George Martin’s lethargic brass arrangement that does nothing for the song but slow it down.

In regards to the crackling noise, could it be the wine bottle on the Hammond Organ again, as it’s heard it in Long, Long, Long? I know that crackling comes from a wine bottle vibrating on top of the Hammond as Paul played it. Seeing as the same organ is used in Revolution 1, it’s a possibility.

Interesting hearing the “take 18” included on the new White Album Super Deluxe edition.

The outro is VERY different than the version unearthed in 2009…

No Mama Dada vocals… and more of the other sounds used on Revolution 9.

For some reason I always thought the “take 2” speech at the beginning was Paul. o u o

I think that crackling noise is the engineer pushing the talk-back key in the control room.

“When George and Paul and all of them were on holiday, I made ‘Revolution [1]’, which is on the LP and ‘Revolution 9’.”

Any idea what John is referring to here? I can understand if he is saying him & Yoko did “Revolution 9” while the rest of them were away, but he seems to be implying he recorded Revolution 1 while the rest were on holiday, and obviously that was done with the rest of the band.

I don’t follow what he is trying to say here? When was the holiday?