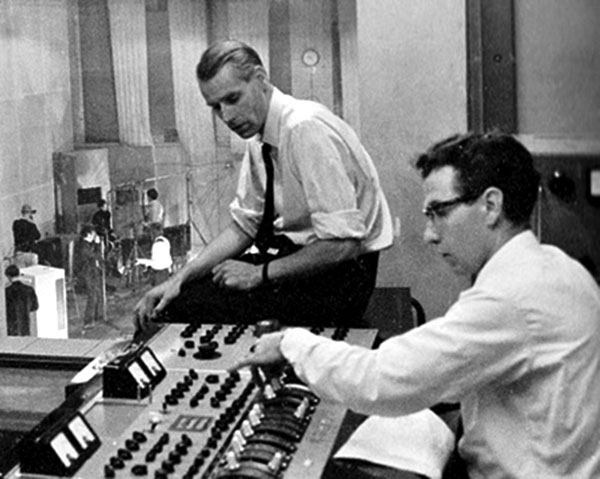

A key member of The Beatles’ music production team at EMI, Norman Smith engineered all their studio recordings until the end of 1965.

Born on 22 February 1923 in Edmonton, Middlesex, Smith served as an RAF glider pilot during World War Two. He had a brief career as a jazz musician before joining EMI in 1959 as an apprentice sound engineer.

I had to start right at the bottom as a gofer, but I kept my eyes and ears open, I learned very quickly, and it wasn’t long before I got onto the mixing desk. In those days every prospective artist that came in had to have a recording test, and that’s what we started doing as engineers, because we couldn’t really cock anything up. Normally, each of the producers at EMI had their own assistants and they would be the ones to keep an eye on the potential talent, and that’s what I was doing when one day this group with funny haircuts came in.

Sound On Sound

Smith quickly progressed to balance engineer, and worked on The Beatles’ recordings from their first artist test on 6 June 1962 until the final Rubber Soul sessions in December 1965. As well as working on their albums, he also engineered their many hit singles during their rise to fame and the peak of Beatlemania.

We all got on so well. They used to call me ‘Normal’ and, occasionally, ‘2dBs Smith’ because on a few occasions I would ask one of them to turn his guitar amplifier down a couple of decibels.

The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, Mark Lewisohn

In June 1965 one of Smith’s compositions was considered for inclusion on the Help! album.

I’d been writing songs since I was a small boy, and in 1965 I wrote one with John Lennon in mind. They were coming to the end of the Help! LP and needed one more song. George Martin and I were in the control room waiting for them to make up their minds and I said ‘I know they’ve heard all this before, but I happen to have a song in my pocket.’ George said ‘Get on the talkback and tell them.’ But I was too nervous so George called down, ‘Paul, can you come up? Norman’s got a song for you.’ Paul looked shocked. ‘Really, Normal?’ – that was one of their nicknames for me – ‘Yes, really.’ So we went across to Studio Three and I sat at the piano and bashed the song out. He said ‘That’s really good, I can hear John singing that!’ So we got John up, he heard it, and said ‘That’s great. We’ll do it.’ Paul asked me to do a demo version, for them all to learn. Dick James, the music publisher, was there while all this was going on and before we went home that night he offered me £15,000 to buy the song outright. I couldn’t talk but I looked across to George and his eyes were flicking up towards the ceiling, meaning ‘ask for more’. So I said ‘Look, Dick, I’ll talk to you tomorrow about it.’I did the demo but the next day The Beatles came in looking a little bit sheepish, long faces. ‘Hello, Norm.’ I thought, hmm, they’re not as excited as me, what’s wrong? Sure enough, Paul and John called me down to the studio and they said ‘Look, we definitely like your song but we’ve realised that Ringo hasn’t got a vocal on the LP, and he’s got to have one. We’ll do yours another time, eh?’ That was my £15,000 gone in a flash. By the next LP they’d progressed so much that my song was never even considered again.

The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, Mark Lewisohn

In February 1966 Smith was promoted to EMI’s A&R department, taking the role that George Martin had previously worked in as head of Parlophone.

Rubber Soul wasn’t really my bag at all so I decided that I’d better get off The Beatles’ train. I told George and George told Eppy [Brian Epstein] and the next thing I received a lovely gold carriage clock inscribed ‘To Norman. Thanks. John, Paul, George and Ringo.

The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, Mark Lewisohn

Smith also worked as a producer, with the Pink Floyd albums Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, A Saucerful Of Secrets and Ummagumma to his name, as well as The Pretty Things’ 1968 concept album SF Sorrow.

In the 1970s he once again tried his hand as a musician. As Hurricane Smith he had a UK number two hit in 1971 with Don’t Let It Die. The recording was a demo Smith had made for John Lennon, but was persuaded by fellow producer Mickie Most that the song was good enough to release as it was.

The following year Hurricane Smith scored a Cash Box chart number one and a Billboard number three hit in the US with Oh Babe, What Would You Say? The first people to send a congratulatory telegram were John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

Hurricane Smith released a series of further recordings, and toured in the UK. However, the hits and his productions became less frequent during the 1970s and beyond.

In 2004 Smith released a new album, From Me To You, featuring re-recordings of some of his biggest hits. The liner notes included tributes by Sir Paul McCartney and members of Pink Floyd.

Norman Smith published an autobiography in 2007, titled John Lennon Called Me Normal. He died on 3 March the following year in East Sussex.

Lovely lad,this Norman

Anyone know the title of the song he wrote in Lennon in mind? Does that demo recording exist anywhere?

Don’t Let it Die

would have been really quite an anomaly; the beatles did cover versions, but only of songs that were already done by other artists. this would have been the only song written *for* the beatles which they’d performed. probably a good thing it didn’t happen…

It’s a pity the Beatles did not make a demo of his song. It could have gone on Anthology and made Norman some money.

When I was writing Norman’s book, he was already fading, and so we had to do it quite fast. But it was fun and we laughed a lot. As far as the song he wrote for John Lennon is concerned he racked his brains for days on end as we sat out in the conservatory. But it just wouldn’t come – Neil Jefferies (‘Research’) down in East Sussex

Has there been any update on what the song was? Perhaps one of the surviving Beatles or someone in the industry at that time knows.

Unpopular opinion: the song he wrote for the Beatles is a myth. There is no way you are going to forget a song the Beatles considered recording and that you were offered 15,000 pounds for. And that you supposedly did a demo of.

Just not believable. I like Smith. Liked his What Would You Say song. But this story is just BS.

Nor is Don’t Let It Die the fabled song: there is no way in eternity that song would have fit in with The Beatles sound or image in 1965.

Sorry, my BS detector is screeching.

Norman appeared to have a relatively good relationship with John, Paul, George and Ringo and AFAIK, he never once denigrated any of their musicianship.

I do disagree with his recollections of the ‘Rubber Soul’ sessions, saying that John and Paul were clashing artistically and Paul was critical of George’s guitar playing, but that’s not true – all four Beatles as well as George Martin had relatively happy memories of the sessions.