3.07am

6 May 2018

Offline

Offline@paintingmyroom, thank you for your input on this subject.

As Matt Williamson remarked above: “Media was there and picked up on this saying the press that it came to blows but this has been refuted by John, George [Harrison] and Mal in separate interviews. George Martin said ‘It came to blows’ though he was not present, having arrived as George [Harrison] was leaving.”

It seems there was some kind of confrontation, but I think it’s quite unlikely that there was a physical fight.

The following people thank Richard for this post:

Sea Belt, RubeAnd in the end

The love you take is equal to the love you make

8.00am

7 November 2022

Offline

Offline@paintingmyroom

@Richard

In the video Richard supplied earlier where Matt plays a bunch of recordings of jams and outtakes, there’s one moment where only George and John are talking back and forth (not Paul and Ringo, at least for some 30 seconds). The talking between John and George is completely unremarkable and doesn’t seem to be about anything special at all, I couldn’t detect any anger, then George suddenly says he’s leaving and make some snide comment and then leaves.

Now in my memory, it was right after that that John said “I’m pissed” and then you could hear him and the other two Beatles begin jamming some angry blues song. However, the apparent fact that they broke for lunch after George stomred out and then came back to jam, if true, indicates that Matt was doing some splicing of the tape and not just playing it all the way through, or the recording itself has been spliced so as to leave out large gaps of time between George storming out, and then the Beatles back in the studio to jam again. If there were a continuous tape and they did go to lunch, one would think after George storms out, you would hear Paul say “What do you think laddies, wanna break for watercress sandwiches?” And Ringo would say “Yeah I’m famished!” and John would say “Yoko? Okay, let’s go.”

Now today I find, you have changed your mind

9.05am

7 November 2022

Offline

OfflineFrom Joe’s page on Lennon’s recording of “Instant Karma ” — a glimpse into what I think is his difference from Paul

Now today I find, you have changed your mind

8.58pm

6 May 2018

Offline

Offline@Sea Belt, the recording wasn’t always continuous at Twickenham Studios, and recording was usually restricted to the large studio area anyway – i.e. generally excluding the other rooms in the complex. I think there is a chronological gap between George leaving and the jam session starting.

The following people thank Richard for this post:

Sea Belt, RubeAnd in the end

The love you take is equal to the love you make

9.38pm

Moderators

Members

Reviewers

20 August 2013

Offline

Offline@Sea Belt, this is the interview bit I keep thinking about – Paul spends lots of time making a record sound just so (recording perfectionism) and he wants people to listen to it on quality equipment.

In an interview promoting “Hope For The Future ,” his new song included in the first-person shooter video game Destiny, Paul McCartney expressed distaste for the way young people consume music through tinny-sounding cell phone speakers.

“In an ideal world, they listen to what you’ve recorded in the way that you have presented it,” the rock legend told the Guardian. “It’s all changed so drastically. A lot of kids listen to music on their smartphones through these tiny little speakers. I’m pulling my hair out thinking, ‘Argh, I spent hours making that high-fidelity sound! Get a decent set of headphones! Please!‘”

McCartney has an analogy for this lo-fi listening experience: “looking at a postcard” of a gallery-worthy painting. “I’d love people to be listening to the music in the most perfect way, so they can experience exactly what we made in the studio,” he says. Still, he adds, if the song itself is of high quality, the “delivery system isn’t important” to young people.

The following people thank Ahhh Girl for this post:

Sea Belt, Richard, Rube, TimothyCan buy Joe love! Amazon | iTunes

Check here for "how do I do this" guide to the forum. (2017)

(2018)

9.55pm

7 November 2022

Offline

OfflineRichard said

@Sea Belt, the recording wasn’t always continuous at Twickenham Studios, and recording was usually restricted to the large studio area anyway – i.e. generally excluding the other rooms in the complex. I think there is a chronological gap between George leaving and the jam session starting.

The following people thank Sea Belt for this post:

sigh butterflyNow today I find, you have changed your mind

11.22pm

6 May 2018

Offline

OfflineSea Belt said

So essentially right at the moment George announces he’s leaving, a second later they switched off the tape.

Not necessarily: John may have decided to leave the large studio area at that point and/or nothing of any significance may have been said after George’s exit (an atmosphere of largely stunned silence would be quite an understandable reaction). The Beatles: Get Back includes only a relatively small proportion of the total footage – about 60 hours of film footage was shot – so there is extensive editing from the available reels.

The following people thank Richard for this post:

Sea BeltAnd in the end

The love you take is equal to the love you make

12.40am

7 November 2022

Offline

OfflineRichard said

Sea Belt said

So essentially right at the moment George announces he’s leaving, a second later they switched off the tape.

Not necessarily: John may have decided to leave the large studio area at that point and/or nothing of any significance may have been said after George’s exit (an atmosphere of largely stunned silence would be quite an understandable reaction). The Beatles: Get Back includes only a relatively small proportion of the total footage – about 60 hours of film footage was shot – so there is extensive editing from the available reels.

Richard said

Sea Belt said

So essentially right at the moment George announces he’s leaving, a second later they switched off the tape.

Not necessarily: John may have decided to leave the large studio area at that point and/or nothing of any significance may have been said after George’s exit (an atmosphere of largely stunned silence would be quite an understandable reaction). The Beatles: Get Back includes only a relatively small proportion of the total footage – about 60 hours of film footage was shot – so there is extensive editing from the available reels.

Now today I find, you have changed your mind

1.42am

6 May 2018

Offline

OfflineSea Belt said

A similar thought came to me in another thread about Paul’s early photographs he took as an amateur shutterbug in the early sixties, where they’re only releasing a certain amount. It seems odd to me, why not simply have two releases: one of them is selective forsome splashy new video or film if people want to make money off it that’s fine, and the other could come later doesn’t have to be at the same time would simply be the totality from which they got it. It’s not like it’s national security issues or something. Now it’s possible there could be personally sensitive things, but they could go through it and make sure that all the living people are okay with releasing it. And if someone says I don’t want that 2 minutes in reel #738 released please, then they can just delete that. I doubt that after that would be done with all the living participants now, there would be very much that would have to be deleted.

For important shots, I sometimes take two or three photos that are closely similar and then select the best of them – because one or two photos might be a little off-centre or slightly out-of-focus, etc.

Paul may feel that some of his early photos are not up to his high standards, and therefore he doesn’t want all of them to be made available publicly?

The following people thank Richard for this post:

Sea Belt, Sea BeltAnd in the end

The love you take is equal to the love you make

7.39pm

2 May 2013

Offline

OfflineTo me the emphasis is different but just as keen:

Witness Paul in Get Back – I want this note played in this way, or this passage slower/faster. Very prescriptive because he knows the sound he wants in his head.

Whereas John would give directions of what he wanted something to sound like: Tomorrow Never Knows – a thousand Tibetan monks chanting; Being For The Benefit Of Mr Kite ! – A thousand fairground organs; Strawberry Fields Forever – both versions are good, find a way to join them; I Want You (She’s So Heavy) – cut it right there; Revolution – overloaded speaker; Instant Karma – drums like wet fish slapping. Perfectionist, but giving a challenge to come up with a way to capture a feeling. What the method is he cares not, it’s the end result, sometimes by happenstance, sometimes engineering brilliance.

The following people thank Old Soak for this post:

Sea Belt, Richard10.43pm

7 November 2022

Offline

Offline@Old Soak

The following people thank Sea Belt for this post:

vonbonteeNow today I find, you have changed your mind

8.22pm

6 May 2018

Offline

OfflineSea Belt said

For example, there’s a passage in Instant Karma where the drummer varies the tempo just for one measure or less. To me it’s a very cool addition, and I wondered did John say “okay I want you to do that at this point.” Or did the drummer just spontaneously come up with it in the moment and John said “yeah let’s keep that in sounds good.”

Here are some comments from the drummer Alan White, who went on to be the drummer for the band Yes from 1972 onwards:

the first studio thing I did with John was ‘Instant Karma ‘.

After that it was Jim Keltner or myself who played on his stuff.

I played on ‘Imagine ‘ and ‘How Do You Sleep’ .

It was all done down at his house at Tittenhurst Park. I spent ten days down there. We’d get up each morning and work in the studio all day. John would come up and give me the lyrics to the song we were doing that day and say, “This is what we are saying to the whole world. You can play on it or not”.

He was very open about things. He’d either have some kind of rough demo, or he’d play through the song on the piano and we’d gradually get into it. Everything seemed to work really well. He’d never say to me, “No, no, don’t play that.” He’d say, “Just play what you feel.”

Everything you hear on the records is what we just got into playing. There was no controlling factor and playing with John was a very friendly, enjoyable experience.

He was very serious about the band and the album. He was totally into it and he knew exactly what he wanted to do. It was as if he had already been through the album in his head and knew what he wanted it to sound like.

The following people thank Richard for this post:

Sea Belt, Beatlebug, RubeAnd in the end

The love you take is equal to the love you make

9.04pm

7 November 2022

Offline

Offline10.44pm

6 May 2018

Offline

OfflineSea Belt said

Thanks, from that description, I would guess the drum patter I’m referring to was a spontaneous improvisation by Alan White which John allowed in and may have even said he liked, but didn’t specify himself.

Instant Karma ! What a great song and vocals from John Lennon with superb drumming by Alan White.

I think it probably was a spontaneous improvisation that John liked. In this video (which has a pre-recorded soundtrack), John gives a look of approval to Alan at 1:46:

The following people thank Richard for this post:

sigh butterfly, RubeAnd in the end

The love you take is equal to the love you make

12.43am

7 November 2022

Offline

OfflineRichard said

Sea Belt said

Thanks, from that description, I would guess the drum patter I’m referring to was a spontaneous improvisation by Alan White which John allowed in and may have even said he liked, but didn’t specify himself.

Instant Karma ! What a great song and vocals from John Lennon with superb drumming by Alan White.

I think it probably was a spontaneous improvisation that John liked. In this video (which has a pre-recorded soundtrack), John gives a look of approval to Alan at 1:46:

Yes, John’s look comes right after the patter I was referring to — though it could have been a look of “You nailed it Alan, exactly what I told you to do!” Probably not though, given the other information you brought.

The following people thank Sea Belt for this post:

Richard, sigh butterfly, RubeNow today I find, you have changed your mind

3.19pm

14 December 2009

Offline

OfflineSea Belt said

On a related note with a different musician, I actually accidentally got to talk on the phone with Lee Oskar, the harmonica player for the soul funk pop band, War.

This is very cool! I love 70s funk bands…how did this conversation happen to come about?

Paul: Yeah well… first of all, we’re bringing out a ‘Stamp Out Detroit’ campaign.

5.41pm

7 November 2022

Offline

OfflineVon Bontee said

Sea Belt said

On a related note with a different musician, I actually accidentally got to talk on the phone with Lee Oskar, the harmonica player for the soul funk pop band, War.

This is very cool! I love 70s funk bands…how did this conversation happen to come about?

It was into the first year of Covid and I was looking for a certain CD he had put out in 1999 which I couldn’t find anywhere, so I saw he had a website that had a contact info including a phone # so I called it, thinking I’d get a recording or at best some support person who probably couldn’t help me. Instead, Lee Oskar himself answered the phone! I think he was hunkering down during Covid. I didn’t want to impose on him so I kept my questions at a minimum — I could have asked him 100 questions! I also asked him if he had ever played with Stevie Wonder, he said unfortunately no, but agreed he’s a great harmonica player. I was able to get the CD, and it has some good tunes, very polished Brazilian type jazz, not his usual. The album cover is clever — two boys, one eating a slice of watermelon, the other playing a harmonica like it’s a slice of watermelon.

The following people thank Sea Belt for this post:

Von Bontee, Richard, sigh butterflyNow today I find, you have changed your mind

6.53pm

11 June 2015

Offline

OfflineRichard said

@Sea Belt, the recording wasn’t always continuous at Twickenham Studios, and recording was usually restricted to the large studio area anyway – i.e. generally excluding the other rooms in the complex. I think there is a chronological gap between George leaving and the jam session starting.

Sea Belt said

So essentially right at the moment George announces he’s leaving, a second later they switched off the tape. It had to have been that quick because it seems like just a second passed before we hear John say “I’m pissed” — or it’s possible they left it on for him to say “I’m pissed” then switched it off immediately, and only turned it back on when they returned from lunch.Such a quick action to turn it off right after he says that or right before seems odd to me. One would think they would leave it on at least for 30 seconds or one minute or something, unless we know that they had a policy, “Okay guys, remember: as soon as they seem to be done with their rehearsal, the very absolute instant that they seem to be done, remember to switch off the tape recorder!” But how would one know when George walks out that they were done? It would have taken several seconds, possibly a minute to know.

@Sea Belt There was a hidden microphone in the cafeteria (I think in a teapot), so the conversation from Monday (after meeting with George over the weekend) was recorded. I think it fills in some of the blanks from the Jan. 10th taping that you are wondering about. The audio is hard to decipher because of the “eating” noises, but this is a good transcription. I’ve included the creator’s notes as they seem legitimate and add to ones imagining of the scene.

January 13th, 1969

roll 132a: the lunchroom tape

As the recording begins, Paul jokingly asks where George is. Yoko remarks that they can get George back into the group quite easily, but John contradicts her, and explains frankly that he doubts this because at the meeting the previous day they’d allowed George’s “wound” to go even deeper – with their egos keeping them from settling things between them.

PAUL: [bleak; joking] So where’s George?

RINGO: It smells like George is here.

YOKO: [to John] Well, you can get back George so easily, you know that. You know, Paul and—

JOHN: But it’s not that easy, because it’s a festering wound—

PAUL: Yeah.

LINDA: Yeah.

JOHN: —that we’ve allowed to – and yesterday, we allowed it go even deeper. But we didn’t give him any bandages. And it’s only because George, uh, when he comes up, when he is that part of him… We have egos. We can’t help but have—

RINGO: Well, it can be a burden.

JOHN: I have, you know—

YOKO: Well, I have one too, you know.

PAUL: You don’t say.

RINGO: [inaudible]

…

JOHN: [inaudible] I wouldn’t say it’s my ego. It was yesterday, really – or, or even the day before when we went to George’s—

PAUL: I sure as hell know I wouldn’t like you to.

JOHN: What?

PAUL: Dig in your heels.

YOKO: Your ego’s great, by the way.

PAUL: ’Cause if I’m to – if I’m to look at either of you, you know, I really don’t like to be smothered. You know—

YOKO: No, no no—

PAUL: You know, if I could–if you were in a shop on a shelf, I might buy you— [inaudible]

John then wonders aloud whether he wants George back in the group at all. He mentions, not for the last time, the inertia that had settled upon the group during the recording of “The Beatles” the previous year, that George is beginning to be unhappy with his role in the group, and agrees with an earlier statement from Paul that George is somewhat apart from the others. The problem with George has obviously riled John, and he apologizes, in a roundabout way, for Paul having to bear the consequences of their conflict.

JOHN: I’m just trying to ask him this time – do I want him back, Paul? I’m just asking, do I want it back? Whatever it is.

YOKO: Right, do you want to have him back. If you want to have George back, you have to—

JOHN: Then if it is, you know, then I’d have to [inaudible] a new one for you, I would have to step in and chance it for you. To carry on, for whatever reasons there is. And so, really—

PAUL: That’s the thing. That’s what I’m trying to do.

JOHN: [inaudible] —has had to go around with more for the past year, than he has – all the other years, because I think he’s been on such a – a good ride before—

PAUL: Could it just be, like—

JOHN: —that like, that he thought he could afford to be more insensitive. [inaudible] —or whatever it was, you know. And this year, he’s suddenly realized it, you know. And—

PAUL: Really? I guess it is. I’m sure it is. I know it is.

…

JOHN: It’s just that, you know. It’s only this year that you’ve suddenly realized, like, who I am, or who he is, or anything like that. But the thing is – you realize that, like, you were saying, like, George was some other part. But up ‘til then, you’d had a – your – your thing that carried you forward.

YOKO: [inaudible]

JOHN: I know, I’d adjusted before you. Alright, that will make me hipper than you, but I know that I’d adjusted to you before that – for selfish reasons, and for good reasons – uh, not knowing what I was to do, and for all these reasons, I’d adjusted to all these, and allowed you to – you know, if you wanted to let me, let me be that guy, very, very… whatever it is. But this year, you’ve seen – suddenly, you’ve seen what you’ve been doing, and what everybody’s been doing, and not only felt guilty about it, the way we all feel guilty about our relationship to each other, is we could do more.

YOKO: [inaudible]

JOHN: I know, the thing is that I’m – I can’t – I’m not putting any blame on you for only suddenly realizing it, see! Because , it might have been our game, you know, it might have been… masochistic, but the – the goal was still the same. Self-preservation, you know. And I knew what I liked about it. I know where – even though I didn’t know where I was at – the table’s there, and… there Ring can do what he wants, and George too, you know…

PAUL: I know. I know—

YOKO: [inaudible]

JOHN: And I have one.

PAUL: But this thing has been—

JOHN: But I think you – I feel it’s—

PAUL: You have—

JOHN: I feel it’s you.

PAUL: Whatever it is – you have. Yeah, I know. Well – well I’ve had [inaudible] as well—

JOHN: Because you – ’cause you seem to have got it all, you see.

PAUL: Mm.

JOHN: I know that, because of the way I am, like when we were in Mendips, like I said – “Do you like me?” Or whatever it is. I’ve always – uh, played that one. So.

PAUL: Yeah.

YOKO: Go back to George. What are we going to do about George?

[John] then explains that he’s torn – part of him wants to help George resolve his problems, and the other half feels that George’s self-imposed exile is well deserved.

JOHN: But this year, suddenly, it’s all happened to you. And you sort of go – you’re take– you’re taking the blame, suddenly, as if, uh… Oh, he’ll say, “Oh yeah, you know I’m a mean guy,” as if I’ve never known it! And then you thought, “Fucking hell. I know what he’s like. I know he used to kick people. I know how he connived with Len, Ivan. I know him.” You know? “Fuck him.” And then, “Oh, but, but right, I’ve done such things…” You know, all that. So you’ve taken the five years that he puts you [inaudible], you’ve taken the five years of trouble, this year. You know. So half of me says, “Alright. I’d do anything to, to save you, to help you.” And the other half of me goes, well, serves him fucking right. I’ve chewed through fucking shit because of him for five years, and he’s only just realized what he was doing to her! So – and that’s something that we’ve – we’ve both known, you know. [laughs; bleak] And it is incredible. [pause]

PAUL: Yeah.

Paul mentions that he assumes that George will return to the group (much as Ringo had the previous year when he’d quit), but John responds and asks him what they’re going to do if that isn’t the case. Paul doesn’t have an answer.

John then repeats a remark George had made at the previous day’s meeting, where (obviously referring to Yoko) he had expressed his opinion that John no longer sees just the four of them as The Beatles. John agrees with George’s assessment, though, and states that he alone could front a version of “The Beatles,” and gives Paul this same credit.

YOKO: But it’s about George. It’s all about George, isn’t it?

PAUL: [restrained] Well, I don’t know, you know.

JOHN: But you see, George – George seems to be—

PAUL: The only thing I can say to that is – the only thing I can say, is just to sort of, [very quiet] you know— [inaudible] —people on – uh. [pause] See, I’m just assuming he’s coming back, you know. I tell you, I’m just assuming he’s coming back.

RINGO: If he wants—

JOHN: What if he isn’t?

PAUL: If he isn’t, then… if he isn’t, then it’s a new problem, in that case.

RINGO: He would like the four of us to sit down.

JOHN: It’s like we’ve said—

PAUL: Yeah.

RINGO: He wants the four of us to actually—

JOHN: See, if we want it – if we do want it, I still won’t tour, man, but I do want to—

PAUL: But you seem to – you seem to think—

JOHN: But if we do end up deciding we want it, as a policy, I can go along with that. Because the policy has kept us together.

RINGO: But the thing is that if we want him—

JOHN: If we want him, because we want him – but the thing is, like George said, it’s that The Beatles, to me, isn’t just limited to the four of us. I think that I, alone, could be a Beatle. [to Paul] I think you could. [to Ringo] I’m not sure whether you could, because you’re doing… Well, like, but I’m just telling you what I think! I don’t think The Beatles revolve around the four people! It might be like a job—

PAUL: But you know what, John, I’ll tell you one thing—

JOHN: [to Ringo] It’s like you joining the band instead of Pete. It’s like – to me, it is like that.

In response, Paul points out there there’s always been a pecking order within the group – that John’s always been the leader, with Paul secondary, and George third. John begins to interject, but Paul stops him, and says that George is correct – and that he and John have connived against him, however innocent their intentions, to keep the status quo. John agrees, and says George has been aware of his conniving since he was fourteen, when they attended Dovedale School together. He feels regret at treating George the way he does, but explains that such behavior is a facet of his personality that he’s tried to keep under control – sometimes going too far in the other direction in accommodating George.

PAUL: Tell you what—

RINGO: [inaudible] Let me tell you what I think. [pause; inaudible] —thing is this. [to John and Paul] You have always been at the front of the chute. Now, there have been some secondary rungs, but George has been third rung, and I’ve been the cabbage.

PAUL: [immediately] Never.

JOHN: [dismissive] No, we haven’t—

PAUL: No, just, no – listen here. You’re the rabbit, he’s right.

JOHN: But not always, though—

PAUL: [anxious] No, listen here – listen – always! Up! Up! [pause] I do think – no, I do think that as grim as it all is, that he’s right. And I do think that like our sole approach is exactly what he’s been saying. And that our brains sort of… con him. It’s all nothing. I do think that is a – I mean— [sputters] As a first way out, I can’t really even say that, but I do think, you know, that when you get right down to it—

JOHN: Yes.

PAUL: ’Cause the moments of clarity, that I’ve just been – are just so innocent, and so simple, that all my connive, and all my – urge, or— [inaudible]

JOHN: But don’t give me like – [inaudible] been aware of my conniving since fourteen. Real aware of it.

PAUL: Sure.

JOHN: And before that. You realize that I’ve known I’ve been conniving from – from Dovedale, you know that. I’ve been aware of that. Just because – I don’t know whether it’s him. It’s not him. It’s just me. That I’ve realized where it’s nowhere – but the thing is, I only know where it is when I’m in the middle of all of it—

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: —that I am sort of at it again. And that’s why I’ve had to fight for the last three years. And I’ve done it – the other way. Just – rather than allow myself to connive, I thought, “Stop it now. Stop it.”

…

JOHN: [whispering] I can’t stand them! The set, and all – all of it. [pause]

PAUL: It’s the same. It’s the same for all of us.

…

PAUL: But you are like that—

JOHN: And I realize that! You might not have realized it, but I have rules, you know. As I’ve taken off – ’cause I have, you know. [pause; somber] And it’s very hard. I kind of… glance it onto me, so it doesn’t harm anybody, you know, which is a – which is a preoccupation, really.

…

YOKO: I respect that I uh, I’m the spectator—

…

PAUL: [trying] If all of you were for sale on a shop, I’d want you as, you know, that, but I really don’t want you as that!

JOHN: Yes.

PAUL: But I want you as that! I don’t want him as that. You see, I want you to want you all. You’re [inaudible]. Now, okay, when I say those things, you know, I can hear myself sort of – but I don’t know what it is you want me to do! In period and in fact, I want you all for whatever you are, because I’m placing it – out of all the best, out of all we’ve bloody done, and what’s best is that what you are, is alright. Because if it isn’t, then it’s stupid of me to keep doing this. You know? Because it’s what you are, and I’ll [inaudible] anywhere. So I’m placing all the money, all the fame, and everything, on what you are. So if this is what you two are, then get on with it.

…

LINDA: [inaudible] —and make a great album, for all you know.

JOHN: But it’s not that easy…

LINDA: Of course it isn’t! [inaudible]

…

They then continue to discuss the dynamics within the group. Paul mentions how they tend to side with one another, and John repeats a statement George has made that he was no longer satisfied to be in The Beatles, because of the compromises necessary to be a member of the group. John mentions how things were still exciting back when they’d made “Revolver ” because they were still surprising themselves with their own music. Now, he feels they’re all working to a formula, and the only way left to challenge themselves is to go solo.

LINDA: You were saying that—

JOHN: [pained] It’s like George said. It just doesn’t give me the same sort of satisfaction anymore. Because of the compromise we’d have to make, to be together. [long pause] You know, it’s that the end result of the records now aren’t… enough. Because now, we – we know it so clearly, how we arrived at it, and for what it was and all. Before, it was always a surprise when we – you know. We weren’t so aware of how we reacted to it. When the – something came out, like Revolver or Pepper or whatever, there was still that element of surprise that we didn’t know where it came from. But now we know exactly where it came from, and how we arrived at that particular noise, and how it could have been… much better. Or it needn’t have been at all. The only way to do it – satisfactory, for y– yourself – is to do it on your own. And then that’s fucking hard.

Linda responds that, whatever the problems with the process, their music is worth it, and that the problems between the band members need to be worked on just like the problems in any relationship.

LINDA: But you were saying yesterday, you know. And you know something, you – you’ve always been sort of thinking that it can’t be any better than it was; you’re not just a studio musician. You always say it. I mean, [inaudible] – I’m saying, hey, you make good music together. And you like it or not, you know.

JOHN: [furtive] I like it.

LINDA: And making good music is also—

JOHN: But it’s just—

LINDA: It’s really hard working at a relationship.

JOHN: I – I know.

LINDA: Of course! That’s what you said yesterday. It happens all the time, you know. And you also said you wanted [inaudible] The Beatles—

YOKO: I don’t want— [inaudible]

John’s not so sure, and mentions that all of them were dissatisfied with the previous year’s double album, “The Beatles,” – not because of the strained relationships during the making of the album, or the quality of the individual numbers (indeed, he thinks the songs are better than those on “Pepper”), but because it was less than satisfactory as a whole.

JOHN: It’s like all of us are dissatisfied with The Beatles LP. Now, it’s not because the way we got on doing it, because the end result was – was as good as it could’ve been. And – I don’t know what the reason could be. [pause] Mal, could you get a little glass of wine?

MAL: Yeah. Red, or—?

JOHN: If I get down to my contributions, then I’m satisfied, you know. But the whole thing is less satisfactory.

PAUL: [to Yoko] Well, I think it—

RINGO: But I enjoy it more.

JOHN: But individually. Name any of them! There is no [inaudible]. Even George’s numbers are more satisfactory than any numbers we’ve done before. But as a whole thing, it’s just not satisfactory to me.

RINGO: Well, I mean, I dig it far more than Sgt. Pepper or anything—

LINDA: You know, it really—

JOHN: And I dig it too. I dig it, individually, far more than Sgt. Pepper . But as a whole – as a Beatles thing, I think it didn’t – it couldn’t work as a Beatles thing. I think it’s one of the best Beatles work we could have, you know, but as a – as an entity, as a whole—

PAUL: [to Yoko] That’s right.

JOHN: —coming out of all of us here – no.

…

Paul, sounding dispirited, remarks that he’s still working to satisfy himself within the confines of The Beatles. He then patronizes John, remarking how John’s his intellectual superior in some ways and, in turn, complimenting Ringo for his idea of recording a solo album of standards (known at this point as “Stardust,” and ultimately released the following year as “Sentimental Journey”). He then makes the touching statement that, when they’re all old, they’ll sing together once again.

PAUL: [restrained] Well, you know. I just think that I… have a lot to learn. And it’s only the simple things I have to learn. Because I’ve learned all the complicated things. And I can hold my own. You know, any [inaudible] types of arguments, with anyone.

YOKO: I know. I know you can.

PAUL: And I can outdo you anytime, I think.

YOKO: Right, right.

PAUL: Because – of the total buzz I’ve been on, that – that I’ve missed the point where I’m on top of a wall, where I’ve got to the top of the [inaudible] and thought, “You’ve won the race!” And I just thought, “But I haven’t.” Because I haven’t satisfied me. I’ve satisfied everyone else. You know. I’ve won the case for everyone else, and I can sort of go up and say, “Ah! But surely, Mr. S.—” “[inaudible]” “Phew. He’s right.” But I haven’t satisfied me. And that’s probably what I meant to say, actually.

JOHN: Yeah.

PAUL: [careful] What I meant to say was… um, a lot of things are just very simple, you know, that I don’t say, because – right, okay, because of certain things, where I have to stop back there, to get this point over. So like, intellectually, I’m – [inaudible] pleased. But I know that I’ve missed a few points, getting on with you intellectually. I’ve missed a few little – things. And that’s why I say, you know, that uh… [to Ringo] Just you talking about the Stardust album – you know. I mean, it isn’t – it isn’t as daft as you were sort of frightened it might sound. It isn’t. It – you know. Or maybe, you know, talking about – I want to see how you really want it to be. I mean, you don’t let me— [inaudible]

RINGO: Yeah.

PAUL: [inaudible] But I really didn’t sort of want to – try to be on your case, by sort of – say, handing you—

RINGO: [inaudible] —just really didn’t like it. And that’s what I’ve said— [inaudible] when I’m singing. “But you don’t sing.”

PAUL: You know, you try and—

RINGO: [inaudible; talking over one another] —and wondering… John might— [inaudible]

JOHN: [inaudible; talking over one another] —all the snobbery— [inaudible] George—

PAUL: [talking over one another; to Ringo] But the great thing is – the great thing is that you singing like how you really sing – will be it. It will be!

RINGO: Yes, but the only way is to do it on your own.

PAUL: Until then – yeah, sure. Until then – until you reach how you really sing, you’ll sing your half-soul.

RINGO: Yeah.

PAUL: And it’s probably when we’re all very old, that we’ll all sing together.

RINGO: Yeah.

PAUL: And we’ll all really sing, and we’ll all show each other how good we are, and in fact we’ll die, then, I don’t know. [Linda laughs; diffident] Probably, you know, probably something sappy or soft like that… I don’t know, but really, I mean, i– it’s really down to all those sort of simple, silly things to me.

YOKO: But those are the important things, you know.

PAUL: It’s got to be simple. It’s got to be simple. It can’t be A plus B equals X plus Y plus Z, because that’s them, you know. And it couldn’t be—

JOHN: [quiet] Maybe that’s what’s evading me.

PAUL: Yes. [sincere] But it’s okay, that, you know.

John’s not sure what the right path is, but Paul tells him he needs to follow the path that seems right to him. John’s still insecure about stepping out of the confines of The Beatles, but Paul once again encourages him to follow his muse. John points out that they’re all confident of their ability to make music on their own.

JOHN: [hesitating] I just, uh… because I’m not really sure what or how I feel about it.

PAUL: No, but you’re—

JOHN: Because any time—

PAUL: You’re unsure because you’re not sure whether to go left or right on an issue. You’ve noticed the two ways open to us. You know the way we all want to go. And you know the way you want to go. Which is positive! ‘Cause you want to go – now, okay. So your positive thing might actually be to kick that telephone box in. It might occasionally be to do that. So you know that’s the way you’ve gotta go.

YOKO: Everybody would want to see that, actually.

PAUL: But you don’t want to actually look like you’re kicking the telephone box in. So you have to sort of say to everyone, “Look at that over there, everyone!” And while they’re not looking, you’ll kick the telephone box in, and sort of— [whistles innocently]

JOHN: I don’t think that’s a fair representation. [laughs]

PAUL: [conceding] Oh, well, it involves me, that’s me. I do that, too. And I think we all do that. But I think the answer is, that – while you’ve got us all looking at nothing over there, and you’ve thrown us for a minute, we would actually all have dug to see you kick that telephone box in. Because we wanna see you do it.

YOKO: But we’d have to say it too, though. That’s another thing.

PAUL: We would actually want to watch the Steve McQueen film, where he kicks the telephone box in. We all want to see that. You know. And I really think that’s—

YOKO: Yes, but sometimes it’s very—

JOHN: But it must be our own faults, that we’ve built it up that I can’t kick the telephone box – apart from it being my fault—

PAUL: You can. You could.

JOHN: But – the feeling that, that – that I – like Ringo said about his album, that what – we’re – you know. I won’t do it, ‘cause I’m gonna let us down, or – look a fool.

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: You know, and we’ve each done that to each— That bit.

PAUL: We all know we can do that, you know. I mean, I’m really trying to sort of learn, really— [inaudible] —meaning.

JOHN: Well, it’s like – we’ve all found – we can do it on our own.

As Paul moves on to a discussion of the current rehearsals, he says that the best he can hope for is approval from two of the three other Beatles. He feels a little guilty about this – as if he could have been better “selling” his songs to the others, and remarks he enjoys getting on the piano, because he’s able to actually perform a song as opposed to rehearsing it, which “sells” it much better.

PAUL: But on our own, I’m just gonna have to sort of just say it to you all. Through the song. Now I know if I – when I’m saying to you all, “Listen, this is how this song goes,” you know, then I know if I half-tell you how it goes, that there’ll be two of you who’ll like it, and then there’s only [inaudible]. You know.

JOHN: Yeah.

PAUL: A certain amount of you will like it, and some of you won’t. Because , and I know – and you know, this is where it gets heavy. Because you’ve got to blame yourself, for that. BecauseI know I half-sang it.

JOHN: Yes.

PAUL: And I know that if – say I’m pissed, at the end of an evening, and I just, and I get on a piano because I really just want to get on a piano. And I’m singing because I don’t particularly want to show off, too. I want to really sing this song, now, and say what I wanna say, and so on and so on and so on. I’ll do it, and everyone in that room will dig it, because it’s me really doing it. And I know that we all have this. [inaudible] And everyone will be really crazy about it. Now if I were really doing it, everyone will listen, and everyone will dig it, and no one will go against it. It’s when I half-mean it, or it’s when I nearly mean it, but there’s – there’s always that one person that can spot that – that—

JOHN: Yeah.

PAUL: Spot them doing a mistake. You know, there’s always someone who can spot that little bit where Charlie Chester didn’t quite mean it, or Charlie Drake, when he didn’t quite mean the joke. You know, it’s all in that.

YOKO: But then sometimes it doesn’t matter to you, so.

PAUL: It’s like if we could really… See, that’s why I think this is where we’ve got a problem now, you know.

[Paul] then offers up another pep talk, and says that if they all just allow each other to play to the best of their abilities and stop trying to micro-manage the rehearsals, things will work out a lot better. John says that Paul can’t make George play competently, because he’s afraid he won’t follow directions, and that Paul treats him the same way. Paul agrees, and John continues with the same subject, only from his own vantage point for his own songs. He says that during the recording of “The Beatles” he felt it wasn’t any use telling Paul how to play, that he (John) was drunk much of the time, and really only concerned about his own singing performance. On top of this, he didn’t want to be seen as providing a finished arrangement for the others – though he claims that “Dear Prudence ” was arranged, as simple as it is.

PAUL: What I’d like to do, is for the four of us – and you know, we’ve all have done that thing, to different degrees – I think, is if you go one way, you go one way, George goes one way, and me another. But I know it will apply to all us, if one day, we can all be singing like we’re singing, [to Ringo] you can be drumming like you’re drumming, George can be really playing – I mean, like he plays, not as if I’m trying to make him play like me. But now it’s like I keep trying to make him play like – how I’ve played – guitar—

JOHN: But you don’t, you see. The point – the point that we both – or, mainly me—

PAUL: Back up, back up.

JOHN: Yeah, okay. Is that – you try and make George play – competently, because you’re afraid that how he’ll play won’t be like you want him to play. And that’s what we did. And that’s what you did to me. [pause]

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: And – I – that’s the difference with you saying that the competent— —so annoyed by the conniving on The Beatles album, was that—

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: I got to a bit where I thought – it’s no good, me telling you how to do it. You know? All I tried to do on that album was just sing it to you like I was drunk, you know.

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: Just did me best to say, “Look, this, this stands up on its own.”

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: And I’m not doing this quite well as I – like even with ‘Don’t Let Me Down’, the first time I sang it. Because I hadn’t allowed meself to say it, as a whole song.

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: I couldn’t work – it was only after we’d done it that I’d realized – it was done. You know, and on The Beatles album, I just sort of said, “[inaudible] —here. This is me singing it drunk, but I’m pretending as if I’m not. What would you do with it?”

PAUL: [laughs] Drunk.

JOHN: You know? “George, you play whatever you like.”

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: You know, and that’s what it was. It wasn’t – it wasn’t the arrogance of, “Listen. This is it, baby.” It isn’t that. I can’t tell you what to do because you won’t play, here, like how I think you should play—

PAUL: Yeah, right.

JOHN: And—

PAUL: You see, that’s – that’s the thing.

JOHN: I’m not going to tell you what to play—

PAUL: That seems to be the trouble, is that—

YOKO: It is. [pause]

PAUL: Okay. And that’s great, you know. And then – just being able to say that, on the occasion. I just mean to say, “Look, I’m not going to say anything about myself, because – we – I’m going to really try, now—”

JOHN: But we’re trying—

PAUL: “—to sing it to you—”

JOHN: [exasperated] Yeah, I know, because you wouldn’t say—

PAUL: Listen to me— [inaudible]

JOHN: [inaudible] —we arranged it, you know?

PAUL: I know, I know.

JOHN: You can’t see— Listen, uh, you— [inaudible]

PAUL: I say that, of course, when— —when you say that to me, because I haven’t got it up off you.

JOHN: Yeah, but the point is—

PAUL: And you’ve sort of – I think—

JOHN: Well, I’m saying that ‘Dear Prudence ’ is arranged. Can’t you hear bom, bom, bom, bom, bom…?

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: That – that is the arrangement, you know.

PAUL: Yeah.

John makes it clear that he doesn’t like directing his numbers the way Paul does, and that he can’t work in that fashion, and never did – though this has sometimes resulted in a recording that he’s not entirely satisfied with (both Paul and John remark that “She Said, She Said” is an example of this). On the other hand, John doesn’t want anyone else to arrange his numbers for him either; but would welcome suggestions that he could either accept or reject as he chooses.

JOHN: But I’m too frightened to say “this is it,” that I just sit there and say, “Look, if you don’t – come along, and play your bit, I won’t do the song,” you know? I can’t do any better than that. Don’t ask me for what… movie you’re gonna play on it.

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: Because … apart from not knowing, I can’t tell you better than you have, what grooves you’d play on it. You know, I just can’t work! I can’t do it like that. Or I could, you know! [quiet] But when you think of the other half of this, just think – how much more have I done towards helping you write? I’ve never told you what to sing, or what to play.

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: You know, I’ve always done the numbers like that. Now, the only regret, just for the past numbers, is that when – because I’ve been so frightened, I’ve allowed you to take it somewhere where I didn’t want—

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: And then – my only chance was to let George or Ring take over, or interest George in it, because I knew he’d—

PAUL: Like ‘She Said, She Said’?

YOKO: Yeah, yeah.

JOHN: ‘She Said, She Said’. Then he’d – he’d– ’cause he’d take it as is. You know? [inaudible; drowned out by voice marking] So on that last album— [inaudible] —arrangements on it— [inaudible] —it’s probably George, you know. If there’s anything wrong with it. Because I don’t want your arrangement on it. I only want your – if you give me your suggestions, where you let me reject them, or in the case there’s one I like – it’s when we’re writing songs.

PAUL: Mm.

JOHN: The same goes for the arrangement. I don’t want it – to… [sighs] I don’t know. [pause]

PAUL: [quiet] No, I know. I know what you mean, yeah.

YOKO: I know exactly what you mean.

JOHN: I want it to be like I’m just doing it, but— —I know— “—dun-dun-duh? Okay, that’s nearly as fast. [inaudible] Or we can go for, duh-duh-dun-dun-duh-duh-duh.”

PAUL: Yeah.

[John] says he’d rather just sing his songs, and let someone else worry about the production (using “Being For The Benefit of Mr. Kite” as an example). Paul says he feels much the same way about his own work, but John points out that at one time neither he or George felt comfortable even offering suggestions to Paul for his tunes, because they were sure they’d be rejected.

JOHN: And that’s all I did on the last album was say, “Okay, Paul. You’re out to decide where my songs are concerned, arrangement-wise.” [exasperated] I don’t know the songs, you know. I’d sooner just sing them, than have them turn into – into ‘Mr. Kite’, or anything else, where – I’ve accepted the problem from you that it needs arrangement. And then, because I’m an ape – I don’t know. I don’t see any further than me, the guitar, and the drums, and – and George Martin doing the— I don’t hear any of the… flutes playing, you know? I suppose I could hear ‘em, if I sat down and worked very hard. I could turn out a mathematical drawing if you’d like, but I could never do it off me own backside, I always have to just – [brushing sound from strumming motion] do that, you know?

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: I mean—

PAUL: [quiet] Yeah. Yeah. [pause] I’m onto the same thing, you know. That’s – that’s – we’re all at that. It is only, like, if you can just remember that we’re – you know. That the four of us are trying to do that. Because I mean, all of those things you say, you know, in some way, apply to me. Not all ways—

JOHN: Yes, yes, because everything applies a little bit to you, too.

PAUL: [inaudible] —it is just you saying it. They’re all – you know, in some way, to some degree, will apply to me.

JOHN: ‘Cause once there was a period where none of us could actually – uh, say anything, about your criticisms.

PAUL: Yeah. Yeah.

JOHN: [bleak] ‘Cause you would reject it all.

PAUL: [quiet] Yeah, sure.

JOHN: And so George and I would just go – you know, “I’ll give you a line here,” “Okay,” you know, “We’ll do four in a bar, and I’ll do…” And a lot of the times you were right.

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: But a lot of the times you were – the same as they always are. But I can’t see the answer to that.

Paul, in his own defense, points out that he’d given George plenty of latitude in the previous week’s rehearsals, but that George isn’t naturally the kind of guitarist who can just improvise a solo, preferring to work it out at home first. Paul then seems to wonder aloud what method could be used with George to avoid the ego-issues raised by their telling him exactly what to play. As they discuss this, the available tape runs out.

PAUL: No, but – no, that’s good you see. The thing is, like, within each other, within – within ourselves, we reach something that’s nearly perfect. And everyone else who’s listening will think, “That’s it. They’ve got it.” You know – you know what I mean. So okay, we know we nearly made it, but – we’ve really made it, for everyone else. ‘Cause it’s okay, we’re into the fine, finest, finest technicalities – I mean, that’s where it’s at, you know. If one day, we can even keep all – if all the people who are listening to this, nearly nearly made it, they’ll think we’ve made it, you know. They’ll think that’s it. So okay, if we can nearly, if we can creep up on it – and that’s – see, that’s what I’m trying to do. Like last week, yesterday [inaudible] doing alright for me, I was really – trying to just say to George, “Take it there,” you know, whereas I wouldn’t have gone [inaudible] and said, “Take it there – with diddle-a-diddle-a-da.” But I was trying last week, to say, “Now, take it over there, and it needs to be like – but, oh, what, like, whatever you—”

JOHN: You see, the point is now – George – is we both did that to George, this time.

PAUL: Mm.

JOHN: And – because of the build up to it, that – now he can’t even take that.

PAUL: Treating him a bit like a mongrel, yeah.

JOHN: He can’t even – you know. It’s like if I say, “Alright, take it,” he’ll say, “Well, look, I can’t take it. I’ll forget it.”

PAUL: Yeah…

JOHN: I have to, uh—

PAUL: ‘Cause he knows what we’re all about.

JOHN: Yeah.

PAUL: So he knows that when we say, “Take it,” we expect doo-doo-duh-duh-doo. If I said that, then you’d expect—

JOHN: But it’s just that bit. The bit where we’ve – ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’.

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: We – there’s no way we could have translated it to him, to say… you know. And then when it came over—

PAUL: Well, if he was desperate, he would’ve just said, “I’ll do it at home.”

JOHN: Yeah. Well, I mean— [inaudible] —nothing to do now! If he’s gonna go home, then so am I, you know?

PAUL: Yeah.

JOHN: I’m gonna go home to record in the studio, rather than go through – through this with anybody in the facility recording me.

PAUL: Yeah, right. But it’s only for a time. [inaudible] —and I’ve never said that to George. I’ve never said to George, “Look, George, I think, now I want this guitar bit, and I want it exactly like how I want it.” And he could have said to me, then, “Well, you can’t have it.”But you see, that’s it. George would never say that to me, and I’d never say that to him, and we go on, just – as separate. But really, I mean, it is gonna be much better if we can actually just [inaudible] and say, “Look, John, ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’, I want you to do this bit exactly like I play it.” And you’ll say, “Forget it, I’m not you.”

JOHN: Yeah.

PAUL: “And I can’t do it exactly like you do it—”

[wip]

?

The following people thank sigh butterfly for this post:

Richard, Sea Belt, Beatlebug, RubeYou and I have memories

Longer than the road that stretches out ahead

9.50pm

7 November 2022

Offline

Offline@Joe @sigh butterfly

If you wrote that, it’s remarkably skillful in capturing the maddeningly inconclusive and elaborately incoherent content of actual recordings like this! The Paul portions are subtly wicked in making him sound a little like the slyly passive-aggressive but nevertheless congenial Gary Cole’s “Bill Lumbergh” character in Office Space

Now today I find, you have changed your mind

12.56am

11 June 2015

Offline

Offline@Sea Belt

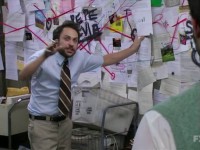

The commentary was written by Dan Rivkin, who runs multiple Beatles sites under the name They May Be Parted. He credits screenwriter Chris Rubeo for the actual transcription. Chris was attempting to write a screenplay based on the Nagra tapes in a failed attempt to sell the idea to Apple Films. Dan is very displeased with Peter Jackson’s editing of Get Back , believing it creates a false narrative. This is a screenshot from his video podcast that documents his issues with the film.

Surprisingly the actual recording is available on youtube.

The following people thank sigh butterfly for this post:

Richard, Sea BeltYou and I have memories

Longer than the road that stretches out ahead

Log In

Log In Register

Register